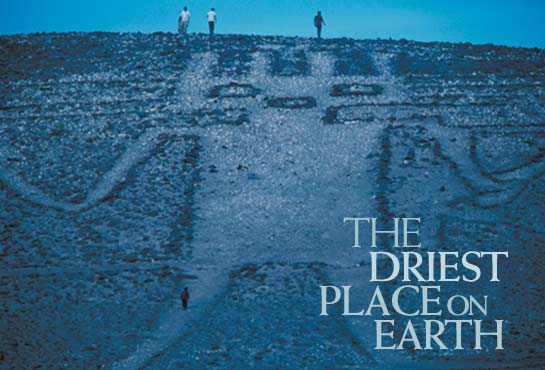

Parts of Chile’s Atacama Desert haven’t seen a drop of rain since record keeping began. Somehow, more than a million people squeeze life from this parched land.

Get a taste of what awaits you on AdventureWomen’s “BEST of Chile: Santiago Wine Country, the Atacama Desert, and Easter Island” adventure vacation as you read Priit J. Vesilind’s article about the Atacama Desert from National Geographic Magazine:

Stretching 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) from Peru’s southern border into northern Chile, the Atacama Desert rises from a thin coastal shelf to the pampas—virtually lifeless plains that dip down to river gorges layered with mineral sediments from the Andes. The pampas bevel up to the altiplano, the foothills of the Andes, where alluvial salt pans give way to lofty white-capped volcanoes that march along the continental divide, reaching 20,000 feet (6,000 meters).

At its center, a place climatologists call absolute desert, the Atacama is known as the driest place on Earth. There are sterile, intimidating stretches where rain has never been recorded, at least as long as humans have measured it. You won’t see a blade of grass or cactus stump, not a lizard, not a gnat. But you will see the remains of most everything left behind. The desert may be a heartless killer, but it’s a sympathetic conservator. Without moisture, nothing rots. Everything turns into artifacts. Even little children.

It is a shock then to learn that more than a million people live in the Atacama today. They crowd into coastal cities, mining compounds, fishing villages, and oasis towns. International teams of astronomers—perched in observatories on the Atacama’s coastal range—probe the cosmos through perfectly clear skies. Determined farmers in the far north grow olives, tomatoes, and cucumbers with drip-irrigation systems, culling scarce water from aquifers. In the altiplano, the descendants of the region’s pre-Columbian natives (mostly Aymara and Atacama Indians) herd llamas and alpacas and grow crops with water from snowmelt streams.

By Priit J. Vesilind, National Geographic Magazine, August 2003